You Should Quit Social Media – At Least For A Little While

And other observations after spending seven weeks away from all the noise.

BY MATT TUTHILL

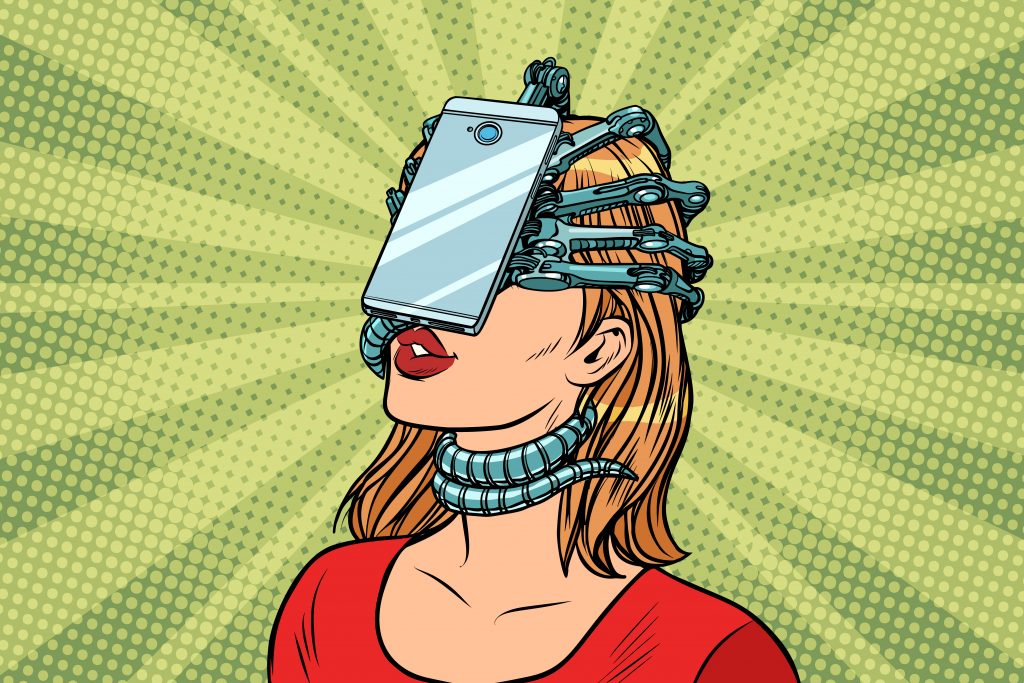

Somewhere along the way, the line between enjoyable diversion and nervous compulsion started to blur. I constantly checked my social media feeds at the first hint of boredom and the time was starting to add up. Finally, and far too long after it had been negatively affecting my daily mood, I decided that I needed to do something about my habit. Social media, I realized, is poison. Not “take one sip and you’re dead” poison, like cyanide. More like “drink this all the time and you’ll feel like a bloated sack of garbage” poison, like soda.

A friend of mine goes on a social media blackout every year during Lent, and his rave reviews of the experience made me want to try the same. I grew up Catholic and while I’m not particularly religious anymore, I’ve mostly stuck to observing Lent; giving something up and trying to live a little more simply, I reasoned, is good for you no matter what you believe.

My initial problem with social media was the same as everyone else’s. Whether you’re on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat, you know how the old refrain “I’ll just check my notifications” so often becomes 20-30 minutes of random browsing. For me, that random browsing didn’t just murder productivity, it usually ended with me taking sides in some bizarre Twitter argument I hadn’t even known existed before I logged on. In short, it made me miserable.

I mainly use four social media platforms—Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn—but my go-to drug of choice has always been Twitter. I created an account in 2010 when I got a job as an editor at a magazine. A colleague of mine was always making great new contacts through the site—plus he always seemed to be way ahead of me on any major breaking news. I took it up and my experience soon mirrored his: it was the perfect platform to promote my work (I previously had none) and network with other journalists and PR professionals who could help me do my job better. I used to have to hunt for publicists and talent through a convoluted web of referrals. It was slow and it didn’t always work. With a Twitter account, I could instantly find exactly who I needed and get an immediate response.

After a while, I didn’t even have to chase contacts anymore. They started finding me.

To my great surprise, it wasn’t just effective, it became a lot of fun, too. I loved logging on during big football and baseball games to spout pithy observations that so tragically would have been lost to the ether without an audience.

I went from “What’s Twitter? That’s stupid,” to posting constantly and building up a modest little following—about 2,800 followers as of this writing. In the world of Twitter, that’s really nothing, but for me it was enough to get a few clicks, sometimes start a conversation, and occasionally have a post blow up when a celebrity shared one of my stories.

The days of Twitter being mostly useful to me now seem too far in the rearview mirror to remember. Gradually, it seemed Twitter became a cesspool of negativity, with every piece of news somehow sparking a fight in the replies.

I reached peak Twitter misery in September of 2016. With the anniversary of 9-11 looming, a mattress store in Texas decided to run a shockingly ill-advised 9-11 sale, and their commercial showcased a couple of employees knocking over two towers of mattresses. The galling lack of empathy for 9-11 victims and their families, combined with the commercialization of what should always remain a solemn anniversary made me nauseous. And so I turned to Twitter for the only thing it’s good for anymore: cathartic release. I tagged the store’s account and told them that if there’s any justice in the world, the coming boycott would put them out of business.

Done and done, right? Given the nature of the store’s transgression and the fact that I didn’t resort to foul language or name-calling (which I wanted to do since I was fuming), I thought I could make my point and stay above the fray for what was sure to become one of Twitter’s patented torch-and-pitchfork moments. A few minutes went by and the replies to my tweet started to roll in. Most of them echoed the original sentiment and added another point or two. A few users, however, told me that I was an old coot with no sense of humor. Then came the kicker: one user told me that I should have died in the towers on 9-11.

Reading this user’s comment made something click for me. It wasn’t that I really thought the guy wanted me to die. It was the fact that he represented the original design flaw of the platform. He was one of Twitter’s millions of anonymous users—a fake name with an anime avatar. Would he say that kind of thing if he had to use his real name? Maybe, maybe not. But was he even real? Was he a bot? Impossible to say.

The real problem, though, runs much deeper than people being able to say whatever they’d like under a cloak of anonymity. Even if you were to ban his account and all others like it, you’re still left to contend with the inherent limitation of the web today, which applies equally to Twitter and Facebook as it does to the comment sections of YouTube or your local newspaper’s website: they all encourage the hottest take you can dream of. They may not have been designed with this conceit in mind, but they adhere to it all the same.

Consider that the value of any Internet comment is measured in likes, shares, and additional replies to the comment. Therefore, it helps your cause—in this case, finding an audience for what you have to say—if you play to an extreme viewpoint or, if going for laughs, say the most outrageous thing imaginable. Hence the extreme corners of Twitter, with alt-right Pepe the Frog lovers on one side and extreme leftist social justice warriors on the other. The fact that the overwhelming majority of people fall in between these two categories is not a reality you’d ever be reminded of if you spent a lot of time on Twitter. That’s because “I see this issue from both sides” is not the kind of sentiment that gets a lot of likes or retweets.

Setting politics aside, even if you’re talking about something as banal and harmless as whichever movie is coming out this weekend, hyperbole is still the rule. A tweet that screams BLACK PANTHER IS THE MOVIE THAT CHANGES EVERYTHING gets a lot more attention than a more subdued take like BLACK PANTHER IS RELIABLE MARVEL FORMULA WITH A REFRESHINGLY DIVERSE CAST.

This general flaw in the web has transformed how editors write headlines, and it’s the reason why a headline for a print publication is rarely mirrored when the story is ported to the web. In print, the reader is a relatively captive audience. On the web, editors have precious few seconds to get your attention as you scroll through your feed. That’s why stories of the bizarre—like an exotic pet attack—which were once relegated to a tiny section of your newspaper, become the major trending stories of the day on the web.

Being aware of these flaws is helpful, but it’s not enough. If you spend a lot of time on Twitter, you invariably find yourself pulled in one direction or another—or rooting for one side to “win” over the other in an argument, even though there is no such thing as a definite outcome.

There’s something to be said, too, for the notion that it seems unnatural to expose yourself to thousands upon thousands of other people’s opinions every single day. If you have a big goal that demands clear focus, it should go without saying that spending a lot of time on social media is one of the worst things you could do.

The only real solution, then, is to spend a lot less time on social media. General mindfulness of your habit might work, but if you’ve got some addictive tendencies, a fast of several weeks is probably the best way to kick the habit. After a fast of seven weeks, I’ve just gotten back into using social media, and, at least for now, I don’t use it the same way I used to. I’m using it less and it’s not my first place to check for news.

Going on the fast was a lot easier than I thought it would be. The first couple of days were tough if only because of my thumb’s muscle memory; out of habit it kept involuntarily reaching for the social app icons at the top of my iPhone screen. A few times I accidentally opened Facebook or Twitter and gasped like I had walked in on someone in a bathroom stall. I quickly closed the apps and luckily after a few days this wasn’t an issue anymore.

After that, the only time it was hard to stay away was on my birthday, which fell 10 days into the fast. I know that 98% of the people on Facebook wishing you a happy birthday are only doing it because they’re getting the same notification about it, but it’s still fun to see who sent you the most creative or thoughtful gif, video, or meme, etc.

What’s more: I started buying physical newspapers again and recognized that when I could simply consume information that wasn’t surrounded with endless commentary, my reaction to bad news wasn’t nearly as visceral. When I sat down with the paper over morning coffee I felt like I was actually learning something about the world, rather than just reacting to its minute-by-minute drama.

It’s kind of sad that it took me—with my degree in communications/sports journalism and 14 years of professional writing and editing experience—a fast of seven weeks on social media to remember what I had always known. There was a reason why, as I was warned about the impending death of print when I entered college in the fall of 1999, that I didn’t budge from my chosen major. I loved print. I may do most of my work in the digital realm these days, but print remains my first love. I subscribe to several magazines that offer digital subscriptions at no additional charge, but I almost never log in to take advantage of this. It’s not the same as sitting with a print edition for a number of reasons, chief amongst them today being the fact that print editions give you a break from the almighty screen and an endless barrage of ions flying into your retinas.

What the fast also helped me re-remember was that in a newspaper, your “feed” is curated by lifelong journalism professionals who don’t—with a few notable exceptions—tend to be reactionary and sensational. As a rule, they also try to balance the information they present in that day’s edition. The contrast between newspapers and Twitter or Facebook couldn’t be more stark; when I compare the two side-by-side today it seems my newspaper was put together by adults. My Twitter “Moments” on the other hand, seem to be aggregated by a gossipy simpleton.

After 10 days of fasting from social media, it was no longer difficult to continue abstaining. I enjoyed more mental clarity and better focus at work. Freed from the torrents of opinions that didn’t belong to me, my writing flowed a little easier than it had of late. Without the light of the cellphone boring into my eyes at bedtime, my sleep improved and so did my energy.

In short, I enjoyed everything a little more, especially the little things: walks with my family, reading books to my son, and running around with him in the park. I’ve always been mindful of not checking my phone when I’m at the dinner table or playing with my son, but eliminating it altogether elevated my parenting to a whole new level of being present. The phone, and everything that came with it, wasn’t just out of sight, but truly out of mind.

The fast also helped me realize that I had tethered a bit too much of my identity to my online persona. I’ve long espoused the idea that you shouldn’t be offended by what anyone has to say unless you know that person very well, love them, or otherwise respect them. Looking back at the 9-11 Twitter/mattress store episode, I realized that by letting myself get so angry about the actions of complete strangers, I betrayed who I aspired to be, acting in a way I had always deemed beneath that of any healthy person. In this instance, my anger at both the store and the flippant commentators was a byproduct of spending too much time on social media. Why did I feel a need to respond at all? The world certainly wasn’t waiting to hear what I had to say about the matter. But constant social media usage tricks you into thinking that an ever-present audience awaits your thoughts. If you indulge the impulse too often, it can become a dangerous trap.

But perhaps the most significant thing I learned during my time away is the fact that not all social media platforms are created equal. I became much more aware of how the different platforms are used, what they’re good for, or what makes them suck. Here are my rankings of the four popular platforms I use, from worst to best. (Note that Snapchat is not on here because I’m 37 and, despite several tutorials from my nieces and nephews, I still don’t know how it works.)

4. Twitter

If I hadn’t already made myself clear, I believe Twitter is the worst social media platform. From the huge number of anonymous accounts to an almost complete lack of oversight of bots and hate speech, its flaws are far more numerous than its benefits. More than any other platform, it encourages hot takes. It’s like a giant barrel of YouTube comments that broke open and spilled over the whole Internet. Comedy accounts and memes mitigate some of the despair. Also, if you have work to promote it can be useful for that. I intend to keep using it, albeit sparingly, for this purpose. But beware: prolonged exposure can become a depression-inducing time suck.

3. Facebook

Facebook is better than Twitter, but not by much. Even if you set aside the double-barreled issues of privacy and the proliferation of fake news, the core user experience is not a good one, offering you a thin line between pleasant nostalgia:

“Hey, I remember that guy from high school! It’s cool that we’re friends on here and I’m happy to see that he’s doing well.”

… and shocking dismay:

“Oh man, I really wish I didn’t know that my distant relative, who I previously liked and respected, hadn’t dismissed the Parkland student protest as the work of paid actors. Oh well. Guess I’ll never be able to look them in the eye again.”

Not only is that line obliterated constantly, but the constraints of the comment section exacerbate the issue. If you were to see your distant relative in person and they were to unveil an abhorrent and demonstrably false viewpoint, you could lay out all the reasons why you believe their viewpoint is misguided, perhaps even over a beer. Doing this face-to-face, of course, is no guarantee that it would end well or that they would give an inch in the debate. But you would get to do this privately—as real human beings with some measure of dignity—and not as perverse performance art for an audience.

No matter how much time you take to consider all viewpoints when you type out a response in a comment section, the format—i.e., it’s not a running conversation between two people, face-to-face—encourages each comment to have a conclusion. (For that matter, how many times have you written an e-mail that was taken out of context or included sarcasm that wasn’t detected?) That’s why so many social media fights are some variation of “Not only are you wrong and here’s why, but you also smell like a donkey.”

The PR literature for Facebook sings a very different tune. It’s all about connecting people and encouraging empathy and so forth. For the sake of argument, I’ll allow that their intentions are in the right place. I don’t think Mark Zuckerberg has any incentive to divide people or give you reasons to hate your distant relatives. But the limitations of his platform—and the web in general—have done exactly that.

2. Instagram

Mostly good and mostly harmless. People might delight in sharing bad news, but on the flip side of the coin is a funny truth: no one wants to take a bad picture. Whether it’s a gym selfie or a shot of someone’s lunch, people mostly want to share an idealized image. Prolonged exposure to idealized images is a separate issue that could give rise to FOMO, or fear of missing out, and depress you in a roundabout way, but it’s less likely than Twitter or Facebook to give you an instant headache.

1. LinkedIn

This is the only social media site I’ll probably never give up—if it can maintain its current trajectory as a vessel for mostly positive content. If people on Instagram don’t want to share bad pictures, the outlook on LinkedIn is even rosier. This is a professional networking site, so your chances of seeing posts where people scream at the rafters about things they hate or espouse fringe political beliefs are slim. I have more LinkedIn connections (about 700) than Facebook friends (about 500) and those 700 people are much more well-behaved than their Facebook counterparts. That’s because they all know a potential employer could be recruiting them on LinkedIn at any moment. Hence everyone puts their best foot forward, sharing inspirational quotes and stories about increasing productivity. In short, it’s one of the only social platforms where you’ll find stuff you can actually use to make your life better. That’s what all of these platforms were supposed to do, wasn’t it?

RELATED STORY The Robert Irvine Power 20 List: Social Media Leaders Who Inform & Inspire

Matt Tuthill is the General Manager of Robert Irvine Magazine, and with the publication of this column, is now a purveyor of cranky old man takes. You can make fun of this column and call him names on Twitter: @MCTuthill.