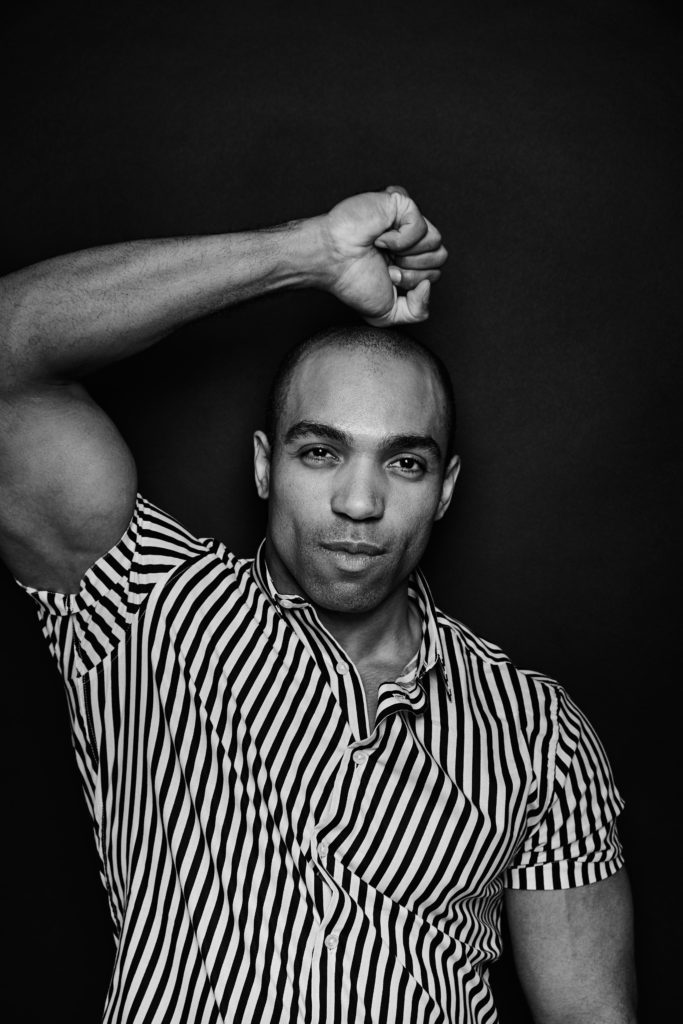

Adam Davenport: The Robert Irvine Magazine Interview

The EDM artist and actor overcame a harrowing childhood and built a career marked by total creative freedom. What he learned along the way holds valuable lessons for us all.

INTERVIEW BY MATT TUTHILL

When a young Adam Davenport realized he was gay, his parents sent him to conversion therapy—and removed his bedroom door to keep a better eye on him when he was home. Despite the intense pressure to change, he emerged from the experience even more certain of who he really was. Fast forward to today and the Yale-educated actor-writer-EDM artist has built a life that so many of us aspire to—one that allows him to chase whatever excites him. He sat down with Robert Irvine Magazine in April 2020, at the height of COVID-19 lockdowns, to talk about how his childhood built him for this moment, his upcoming projects, and making peace with his parents. The following interview has been edited for content and clarity.

RI MAGAZINE: How are you holding up right now? And how is the pandemic affecting your work?

AD: I live in Battery Park, two blocks from Wall Street, so it’s very quiet here. I haven’t gotten sick, but I know quite a few people here in New York who have gotten sick. A few of them didn’t make it, unfortunately. No one who I was close to in my immediate circle, but I feel like it’s a reminder to focus on things that are in our immediate control. So, I’m trying to use this as a gifted time and I’m finding ways to be productive.

There are a few projects that I’m still in development on. There was a film that I that I co-wrote, and I’m directing, and also acting in. So, I’m still putting energy in that and there are early pre-production tasks, that we can still do like make offers. The good thing is that actors are reading right now because nothing is shooting. So, I’m just trying to use that to my advantage.

I just finished a new track during this time, too. It’s a collaboration with another producer, Kraiz; he’s a big headliner DJ in Asia. So, we just tried to use this time meaningfully to work on that song.

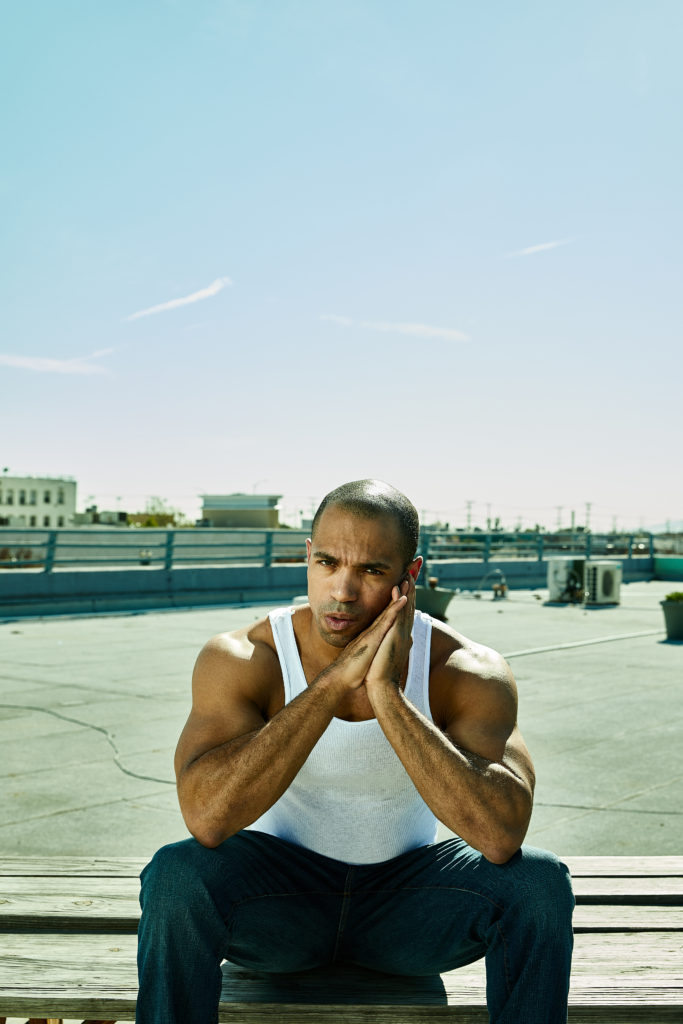

I’m also really into fitness. Knowing that the gyms were going to close, I invested in this home project that turned the living room into a home gym. I have a squat rack in there now.

RI: Fantastic.

AD: There’s also a new project that these filmmakers are writing for me. I would describe it as a gay version of Misery, the horror film with Kathy Bates… So in this, I’m playing the personal trainer from hell. I’m hired to move me into this guy’s house in the Hamptons, to train him every day and get his nutrition straightened out. The relationship immediately is codependent and then toxic. Then it becomes a horror movie.

RI: That’s a great setup.

AD: In that character’s mind, he’s doing what he needs to do to have the client reach his goals… It doesn’t really have a title yet. Right now we’re just calling it Personal Trainer.

RI: And the one that you wrote and are pushing into production when things get back to normal?

AD: That’s Tar Baby. It’s set in a small town in West Virginia that’s become the epicenter of a heroin epidemic. There’s this autocratic sheriff who’s running for re-election, and she’s running her entire messaging for her campaign as down with drugs. The campaign’s imbued with racism. My character, I live with my father on the outskirts of town, and we’re the only black family in town. And rumor has it that the nursery that I run is just a front for my drug dealing, that I’m the one who’s supplying the community with heroin. But she’s just trying to find a way to essentially get the black people out of town.

Where the genre element of the script comes in is all these people are overdosing from heroin and they discover this organism on their bodies that resembles tar. From there it gets wild.

RI: Your song HYPE is a look at social media and how we’re too addicted to it. Does the current situation with lockdown have you looking at some of the positives and how it can keep people connected?

AD: Nothing is completely black or white. Everything, whether it’s social media, sexuality, or anything that has any level of complexity, there’s gray. So I think that song focused on the culture of superficial that pervades social media. It can also be used in a very powerful, and meaningful way. I think I struggle with finding the balance, and finding where you can differentiate yourself from the superficial.

So, I think in that one song that was where I was at in that moment in time.

RI: Are you finding inspiration in this moment we’re living through?

AD: Well, I think the personal trainer horror movie deals with one theme of this pandemic, which is this idea of how people deal with isolation, how isolation shapes us in both positive and pejorative ways. Unplugging from the external world does can invite introspection and self-examination. So there is that duality, because loneliness can be very hard… As an artist anyways you’re always going to be drawing from a combination of personal experience, imagination, and sometimes drawing things from the outside world. I think that’s how I’ve always operated. So I don’t know that it’s going to change my, fundamental approach to things.

RI: You grew up in a very poor, rough area. I’m curious if growing up with so little made you better able to weather this current situation? Are you, maybe more than other people, able to say, “This is enough and I’m good.”

AD: Well, even as recent as early-adult, I’ve gone through periods of being without. When I first to New York 2016, my first two years I was on EBT and food stamps because I made a decision to support myself solely as an artist. I wasn’t going to have a survival gig. I found this hole in the wall in Bensonhurst that rented me a room for $500 a month as the work that I was able to get at that time. I had to live on very limited means for two years. So as you know that’s humbling as someone in their early thirties with an Ivy League education.

But yeah, I think that being accustomed to being without started in childhood, but I’ve also been poor as an adult.

RI: You also overcame conversion therapy. How did you get into that? And did you commit to any of it before rejecting it?

AD: I was 13 years old. I just graduated from eighth grade and was going into my freshman year of high school. My parents, more or less what happened, is they found out I was gay. They demanded it.

RI: You didn’t come out to them, they found out through some other way?

AD: Well, they found two pieces of evidence. You remember when America Online sent free trials? Like floppy discs?

RI: Yes.

AD: So I was like, “Well I have all these extra disks.” I reformatted them and I was a … lonely 13-year-old. I would download… just jpegs, no videos. Pictures of … guys that I found and they were all muscular. I collected these images because I was fascinated to look at them, and so they found them. Then the other evidence a journal I had. Some of it was my thoughts, but a lot of it was just lyrics from INXS or The Velvet Rope like, they were my thoughts, but largely they were just like plagiarized lyrics from INXS or The Velvet Rope or Fiona Apple’s Tidal – there was some erotic stuff on there. I could just identify with those lyrics. I just changed the gender pronouns and stuff, and I’d just collect these lyrics and write them down, but you know if my parents weren’t that pop culture savvy.

RI: They thought you were writing all of it.

AD: When they confronted me, I felt my privacy was completely violated. So for about three months to this doctor. I was not that down with it. I was uncomfortable when we first went, they didn’t even tell me where we were going, just that we were going to the doctor. And in your first few sessions, they don’t tell you it’s conversion therapy.

At first the doctor was trying to get a sense of my sexual narrative—like had I done anything at this point, but I was still a virgin. But finally, he sat them down one day and said this is only going to work for for anyone if they want to change. And when he concluded that I had no desire to change., he recommended family therapy. But of course there was nothing wrong with me.

So I resented my family for a really long time. Because my parents engaged the rest of my family to deal with the problem. My grandfather and my dad had me read literature from the 1950s that said homosexuality was a mental disorder. My uncle and his wife came and made me read Leviticus out loud, trying to make me believe I was going to hell. Then my parents took the door off my room a few and I always felt like I was under surveillance.

I just kind of coped with it by burying myself in my schoolwork. I had really good grades. I got in too early. I was probably over committed to extra-curriculars. But believe it or not I have a good relationship with them now. They met my first boyfriend in New York a few years ago.

I’m able to talk to my mom now about guys I’m dating. So we’ve come around. The world was very different in 1997. Absolutely. They both love me. We’ve come a long way so I want to I don’t want to throw them under the bus, but those things did happen.

RI: That’s a great story. Have you ever written it down?

AD: I have. And I’ve had this conversation a lot with a lot of people, people who have also suffered, so one I’ll write about more, a coming of age story. But I have to get my thoughts down.