LIVING LEGEND: The Story of Hershel “Woody” Williams

His heroism in World War II earned him the Medal of Honor, but that was just the beginning of his story. At home, he faced a brand-new battle. Here’s how he won both.

BY MATT TUTHILL

In the two decades after Woody Williams came home from the war, he was the man everyone expected him to be. He was productive and respected at work. He was loved by his wife and two children. Day after day, he went about his business, betraying no hint of the emotional burdens and mental scarring he endured on the front lines of one of World War II’s bloodiest battles.

Williams, now 94 years old and the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Iwo Jima, and the last surviving Marine to have won the honor in World War II, is at ease speaking candidly about his experiences. But for 17 years after the war ended, Williams didn’t share much about his time overseas. Nor could he forgive himself for the many lives he took, and the manner in which he took them—at close range with a flamethrower.

“I had a tremendous amount of difficulty because I couldn’t forgive myself for having to take so many lives in such a horrible, horrible way,” Williams says today, speaking from his home in West Virginia, where he lives alone. (He lost Ruby, his wife of 63 years, to a heart attack in 2007.) “A person’s life taken by flame is so, so horrible. There is an odor that emanates from that, that is like no other odor on earth. And sometimes, in the years after, there would be something, an odor from somewhere, that would bring that back to me.”

From 1945 to 1962, Williams pushed the feeling away with gallons of beer at his local VFW. “It is just what you did,” Williams says. “And I kept fighting the demons. I finally went to God to see if I could find some release and some forgiveness for what I had to do. And I found it.”

For today’s veterans and civilians, it is instructive to hear Williams speak about his battle experiences and the difficulties he faced afterward. The anxiety, remorse, and flashbacks he dealt with after the war is not unlike the many cases of battle-induced post-traumatic stress disorder of today, though Williams was never diagnosed with PTSD because the term didn’t exist at the time.

We often associate battlefield trauma with veterans of Vietnam and all subsequent wars. This isn’t so when we think of the soldiers and Marines of the Greatest Generation, if only because so few men of that time spoke publicly about the true nature of what they did and what they saw, much less how it made them feel. Gender roles through the 1950s were rigid, and in regard to expressing emotions, very simple.

“I can remember my dad telling me, ‘Boys don’t cry. Man up and don’t do that. Women do that,’” Williams says. “We may have cried, but we didn’t do it openly.”

Williams was raised in the tiny community of Quiet Dell in Marion County, West Virginia. He was taught in a one-room school and his parents ran a local dairy. He was 17 years old when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, working in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal work program which was dissolved soon after the U.S. entered the fray of World War II.

He tried to join the Marine Corps right after the attack, but his mother refused to sign the papers to let him in underage. When he was 18, he attempted to join on his own, but being only 5-foot-6, the recruiters rejected him; he was two inches shy of the minimum height requirement. By May of 1943, however, the strain on the military was significant enough to ease those standards, and Williams became a Marine.

By December of that same year, Williams was sent to Bougainville in the South Pacific, arriving shortly after Allied forces took the island back from the Japanese. He then joined the Marine Third Division in Guadalcanal, the site of the first Allied victory, and trained there until June of 1944, when he saw his first combat in Guam. He stayed stationed there after the victory until February of 1945, when he was sent to Iwo Jima.

That infamous battle lasted more than a month, from February 19th to March 26th. It was a long slog for the Allies, owing mostly to firmly entrenched Japanese forces. The battlefield was littered with reinforced concrete pillboxes, which were designed with tiny slits to allow the enemy to shoot in all directions. But these slits were so small they barely qualified as a weakness. The Japanese position was impassable for Allied tanks, never mind infantry on foot.

“We lost so many Marines attempting to approach those pillboxes,” Williams says. “Our commanding officer lost most of his officers. We had lost our platoon leaders. We had lost our squad leaders. We had people doing jobs that they were never trained to do because you lose so many people and somebody takes up the slack.”

On the morning of February 23, Williams’ commanding officer called a meeting of surviving officers.

“I wasn’t supposed to attend that meeting,” Williams says. “I was a corporal and corporals do not attend meetings of that nature.”

But for some reason, Williams’ Buck Sergeant told him to go and he complied. The Marines gathered in the center of a bomb crater—the high walls around them provided good cover—where the C.O. admitted he was out of ideas.

“‘What are we gonna do?’” Williams recalls him saying. “‘Every time we advance they beat us back.’ That’s when he asked me if I could use a flamethrower to get rid of some of those pill boxes.”

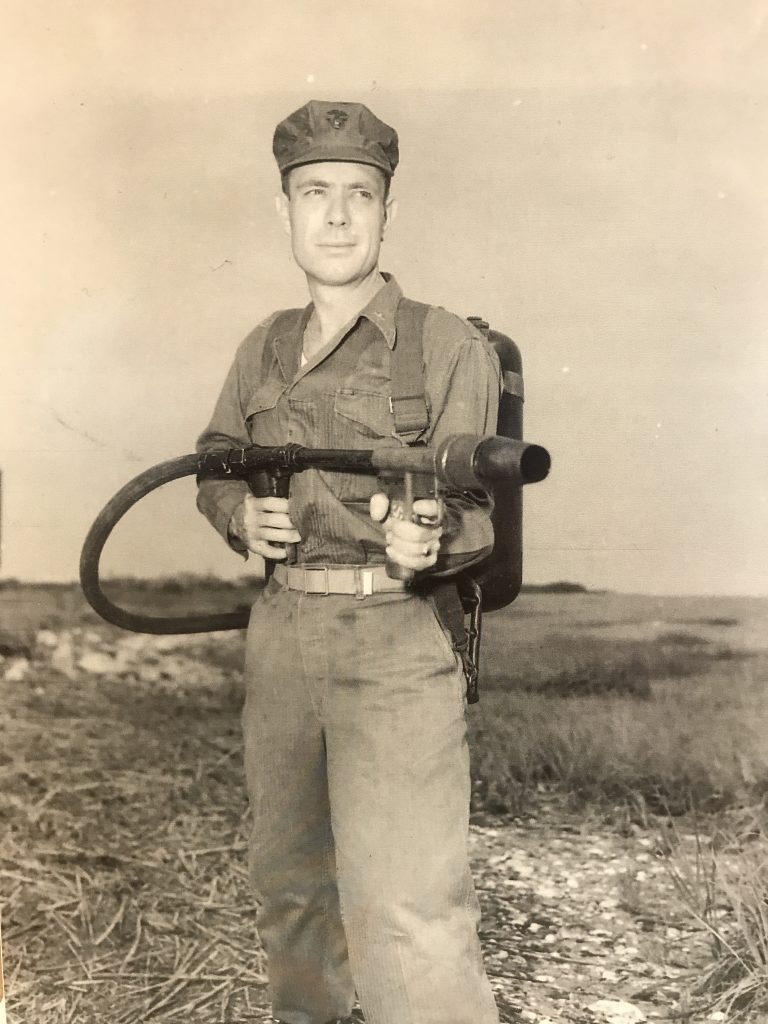

Williams agreed, and over the course of the next four hours, with a flamethrower tank strapped to his back, he crawled on his belly toward the pillboxes, with four Marines providing cover fire. When Williams got close enough to the enemy position, he discharged his flamethrower to kill the soldiers inside.

It was an effective strategy, but Williams became a big, slow target, one whose position was telegraphed every time he fired his weapon, which billowed telltale black smoke to the entire battlefield.

“When you fire a flamethrower, you give off an awful lot of black smoke because you’re burning diesel fuel and gasoline,” Williams says. “Other Marines trained me to do this, otherwise I wouldn’t have done it; when you fire, you move from that particular position because that’s where they’re going to start dropping the mortars.”

Though Williams says he crawled on his belly most of that afternoon, he did have to stand up a few times. One of those is mentioned in his Medal of Honor citation; Williams saw a small amount of smoke emanating from the top of one of the pillboxes. Realizing it was a vent, he crawled in close to the box, stood up, and climbed on top.

“I figured there was an opening up there and a good way to kill the people inside was to shoot the flame down through that hole,” Williams says. “And that’s what I did.”

When Williams landed on Iwo Jima, there were six men under his command. “Flamethrower demolition guys,” he explains. “Privates and PFCs under my patrol. I was their man. And my job was not to take their place but to keep them in supplies and make sure that the flamethrowers are ready to go. Make sure that the explosives are ready to go. That they’ve got everything they need because they were my group. By the 23rd, I didn’t have any left. They were all gone. Wounded or killed, I never did know. I never got a report.”

With no other Marines trained to use a flamethrower, Williams’ mission continued as a solo effort under cover fire; each time his flamethrower ran out—the four-and-a-half gallon fuel tank was good for just 72 seconds of sustained burn—he retreated behind his own line to get a new one and to set demolition charges to clear a path for the tanks. At least that’s what his citation says. Williams says he can’t remember how he obtained the new flamethrowers, nor how long the process took.

“I have talked to psychologists about why I can’t remember going back to get five more flamethrowers,” Williams says. “I used six flamethrowers that day, I’m told… And for four hours, they tell me. I could not have imagined how long because there’s no time frame, nothing to measure by. Night and day run together. You don’t know what day it is and you don’t care what day it is.”

He’s also hazy on how many enemy combatants he killed, because, he says, “you never knew how many Japanese were in a pillbox. Sometimes it would be a great number. Sometimes it would be a few. One report that I saw, by the witness of another Marine, said there were 17 Japanese in one of them. I couldn’t confirm it. And I’m not particularly interested in knowing how many.”

Frequently, Williams made his way to the rear of the pillbox to clear it out. On one occasion, an enemy infantryman charged at him with a bayonet and Williams killed him with his flamethrower.

While Williams cleared the way for tanks that day, Marines elsewhere on the island raised the American flag atop Mount Suribachi, a moment immortalized in monuments and photos. He continued to fight through the end of the battle, and was wounded on March 6 and earned the Purple Heart.

The war ended on September 2 of that year. In a White House ceremony on October 5, President Harry Truman pinned the Medal of Honor on Williams’ chest. By rights, it should have been a crowning achievement, but Williams’ inner battle was just beginning.

Shortly after the war ended, he lost his older brother Gerald, who had seen extensive combat in the Battle of the Bulge, and was “shot up bad” according to Williams. “They kept him in a mental hospital until March after the war was over, because they didn’t think he was capable of coming home and taking care of himself. He cracked up. Went all to pieces… He just gave up life. He wanted to die, and he did, not too many years later.”

In addition to his brother Gerald, Williams had another older brother, Lloyd, who served but thankfully didn’t see combat as part of a rear supply chain in Germany.

Williams stopped suppressing his emotions with alcohol in 1962. That’s when he found God through his wife’s Methodist church. Until that point, he hadn’t been a churchgoing man, but the religious experience changed him forever. He quit smoking, drinking, and even swearing, committing himself to God and his family. Later, he took on a new career, that of veteran counselor, a job he held down for 33 years.

“It was one of the most rewarding jobs that anybody could possibly have,” Williams says.

The Medal of Honor, he adds, gave him extra incentive to live the fullest life possible and be the best version of himself he could be.

“I no longer just represented me,” he says. “I now represented the Marines who protected me, Marines who sacrificed their lives doing that… If I had written that recommendation for the Medal of Honor—which I didn’t, my commanding officer did—I would have never used the word ‘alone.’ I sort of resent that word in my citation. It says, ‘He went forward alone.’ That’s not correct. Four Marines were protecting me, and two of them were killed while they did it. So I have said from the very beginning that it does not belong to me. It belongs to them.”

When asked if he could have better dealt with the trauma if men at that time weren’t tacitly forbidden from talking about their feelings, Williams replies succinctly, “Oh my, yes.”

Basic resources for veterans, he adds, were scarce.

“When I think back to the World War I veterans who came home shell-shocked, they had nowhere to go,” Williams says. “There was no VA (The U.S. Office of Veterans Affairs). The VA wasn’t created until 1930. After World War II, when we came home we had no psychiatrists. We had no social workers. I lived in Fairmont, West Virginia, and the only VA medical hospital in the state was 220 miles away. I couldn’t have traveled 220 miles for treatment.

“I’ve never seen a record, and I’m not sure there is one, of how many suicides we had after World War II. But those individuals had no place to go. No one to talk to and no hope.”

Williams says that the seemingly endless military conflicts of today underscore the need to unify in support of the troops. It has been established that 22 veterans commit suicide every day. For Williams, it is a galling statistic, but it’s also an opportunity to unite for a common cause at a time when the country desperately needs it.

“We take it for granted that it’s just another job,” Williams says. “It is not another job. I don’t go out every day and risk my life in any way. They do it without question, with everyone being a volunteer… We have to believe in what they’re doing. There are a great number of people in the country who are not quite sure that we should be involved in some of the combat situations that we’re in. I guess that’s pretty typical. But as a result of that, we lose our perspective about the sacrifices that are being made.

“In the Marine Corps in World War II, we had a word that we would greet each other with. if somebody would do something outstanding, we’d say, ‘Gung ho!’ Today I guess it’s ‘Oohrah!’ In my day it really meant ‘together,’ ‘We are together.’

“If America doesn’t come back together, we’re gonna lose it.”

GOLD STAR MEMORIAL

In 2010, Williams founded The Hershel Woody Williams Congressional Medal of Honor Education Foundation, Inc. It is a charitable 501(c)(3), not-for-profit organization that pursues specific endeavors and goals through the vision of Medal of Honor Recipient Hershel “Woody” Williams. The Foundation encourages, with the assistance of the American public and community leaders, establishing permanent Gold Star Families Memorial Monuments in communities throughout the country and provides scholarships to eligible Gold Star Children. (A Gold Star Family is one who has lost a service member in combat.) Its purpose is to honor Gold Star Families, relatives, and Gold Star Children who have sacrificed a loved one in the service of their country.

The Gold Star Families Memorial Monument preserves the memory of the fallen and serves as a stark reminder that Freedom is not free. The stunning black granite monument features two sides. One bears the words: Gold Star Families Memorial Monument, a tribute to Gold Star Mothers, Fathers, and Relatives who have sacrificed a Loved One for our Freedom. The other side tells a story through the four granite panels: Homeland, Family, Patriot, and Sacrifice. The scenes on each panel are a reflection of each community’s Gold Star Families and their fallen heroes. At the center of this tribute is the most distinct feature of the monument, the cut out which represents the loved one who paid the ultimate sacrifice in the name of Freedom.

To date, 26 monuments have been completed and 51 are in progress. To help fund the work of Woody’s foundation, click HERE.

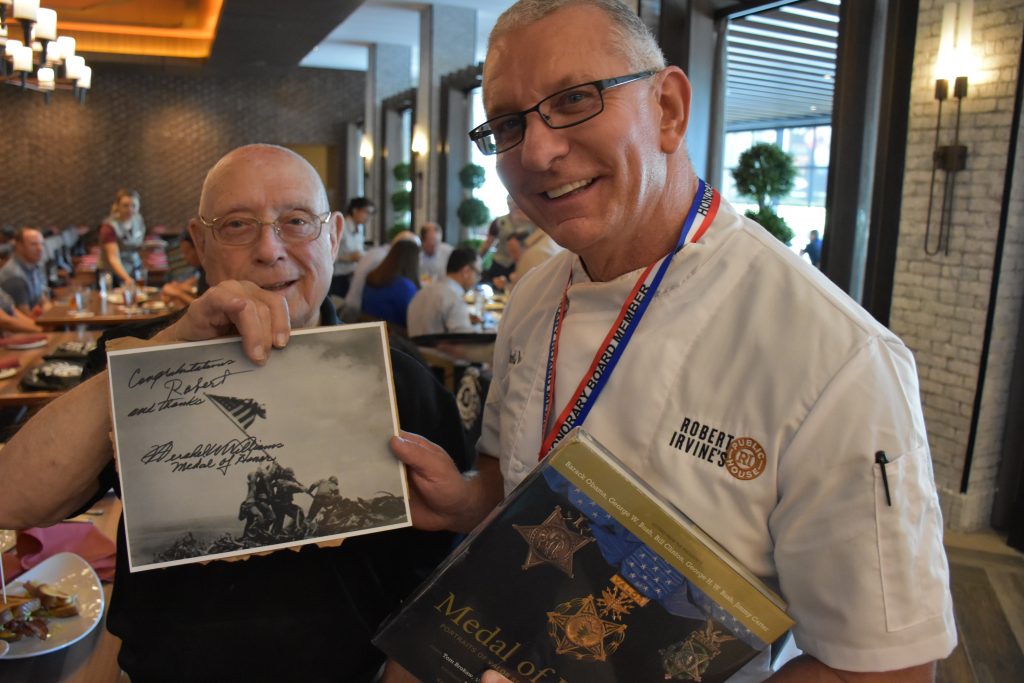

FRIENDSHIP WITH ROBERT

Williams accompanied Robert on his helicopter ride as he arrived at the grand opening of Robert Irvine’s Public House at the Tropicana in Las Vegas in July of 2017. Williams also gave a speech introducing Robert and thanking him for his dedication the USO and for the charitable of The Robert Irvine Foundation. The two had previously kindled their friendship at a benefit for the troops where Robert cooked and made a guest appearance.

Williams was welcomed with a rousing speech by Tropicana GM Aaron Rosenthal, who detailed the actions that earned Williams the Medal of Honor. When Williams took the microphone, he said simply, “Today isn’t about me. It’s about Robert and the incredible things he’s done for veterans.”

After the dedication speeches at Public House were over and Williams could get Robert away from the crowd, he presented the chef with a gift—an autographed copy of the famous photo of the flag raising at Iwo Jima, this BOOK about the Medal of Honor, as well as a medal naming Robert an Honorary Board Member of Williams’ foundation.

Robert was touched by the gifts, and humbled by Williams words.

“I know the restaurant has my name on the front, so obviously people are going to get up and talk about you,” Robert says. “Of course you’re going to be flattered. Of course people are going to present your best qualities and accomplishments. But when they come from a man like Williams—a true legend, a true hero, who did such incredibly brave things for this country… well, when he started listing my accomplishments as if they were of equal value, it was too much for me. I know that nothing can ever compare to what he did. But that’s how humble he is. That’s how gracious he is. They just don’t make them like him anymore.”

To support the Robert Irvine Foundation, which disperses grants to veterans and veteran causes in need, click HERE.

CITATION

The official Medal of Honor citation for Woody Williams reads as follows:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as demolition sergeant serving with the 21st Marines, 3d Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, 23 February 1945. Quick to volunteer his services when our tanks were maneuvering vainly to open a lane for the infantry through the network of reinforced concrete pillboxes, buried mines, and black volcanic sands, Cpl. Williams daringly went forward alone to attempt the reduction of devastating machinegun fire from the unyielding positions. Covered only by 4 riflemen, he fought desperately for 4 hours under terrific enemy small-arms fire and repeatedly returned to his own lines to prepare demolition charges and obtain serviced flamethrowers, struggling back, frequently to the rear of hostile emplacements, to wipe out 1 position after another. On 1 occasion, he daringly mounted a pillbox to insert the nozzle of his flamethrower through the air vent, killing the occupants and silencing the gun; on another he grimly charged enemy riflemen who attempted to stop him with bayonets and destroyed them with a burst of flame from his weapon. His unyielding determination and extraordinary heroism in the face of ruthless enemy resistance were directly instrumental in neutralizing one of the most fanatically defended Japanese strong points encountered by his regiment and aided vitally in enabling his company to reach its objective. Cpl. Williams’ aggressive fighting spirit and valiant devotion to duty throughout this fiercely contested action sustain and enhance the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.