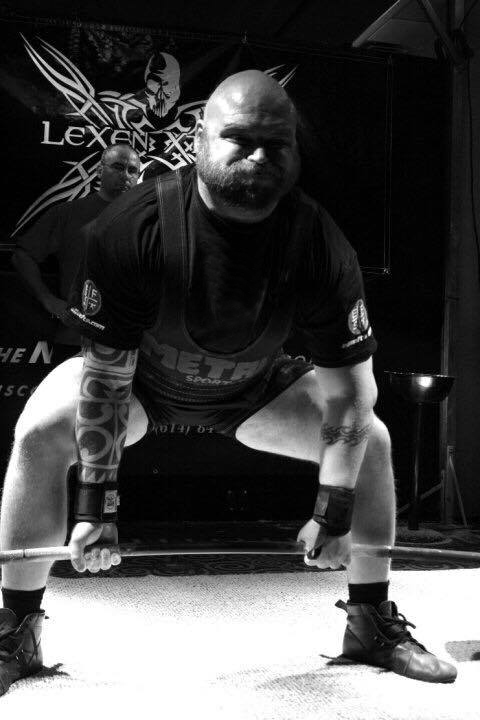

The Unstoppable Jason Pegg

Gravely wounded in Afghanistan in 2005, Jason Pegg found a new lease on life through powerlifting.

BY MATT TUTHILL

The good will mission was like any other he had been on. Army Sgt. Jason Pegg was providing security for a medical assistance program where his unit escorted doctors, dentists, paramedics—even veterinarians—through small Afghani villages to bring aid to the locals.

“The Taliban would tell them that Americans were there to kill them,” Pegg says. “We did this kind of community outreach to prove that we weren’t.”

After two days of visiting villages, Pegg rode with his unit in a Humvee to their final destination. While en route, an IED exploded, ripping through their vehicle. His memory of the aftermath is hazy.

“It was loud and there was a lot of dust all of a sudden,” he says. “Honestly, the roads are so bad—and we often blew out tires—that I thought we had blown another tire.”

Then he heard his platoon leader shouting into his radio calling for help–and he saw the blood spattered throughout the vehicle’s interior—and finally realized what was going on.

Miraculously, no one in the vehicle was killed, but there were serious injuries; the driver lost an eye and the soldier manning the turret suffers from memory loss today. Pegg is lucky that his helmet did its job, absorbing shrapnel that was otherwise headed for his brain.

His left arm wasn’t so lucky.

“My arm was pretty close to coming off,” Pegg says. “There was a lot of soft tissue loss and severe fractures in all three bones, including a radial fracture in my ulna.”

Doctors succeeded in saving the arm, but Pegg spent the next 18 months in Walter Reed recovering. The way the arm healed, he can no longer pronate or supinate his hand. It’s “stuck in neutral” with his palm facing inward. Range of motion is also very limited—from 90 degrees to about 110.

During his first day or two at Walter Reed, stray thoughts came into his mind. “Why did this happen to me?” “We were almost done with the mission…”

Those thoughts stopped immediately when he was visited by two other patients.

“One had lost his right leg above the knee—it was six inches long—the other guy had suffered severe burns all over his body including his face. He was missing his ears.”

Despite the seriously debilitating nature of their injuries, they didn’t carry one iota of self-pity, and they wanted to know what had happened to Pegg.

“Those guys came in and were cracking jokes,” he says. “When you see that—not just their injuries but their attitude—you say ‘Ok, it’s not that bad. It’s really not that bad. I can deal.’

The recovery process was still a long slog. At one point, he only had a two-inch range of motion on his left arm. Physical therapy gave him time to think. Pegg had always been athletic (he played a year of D-I football for Ball State before leaving for the Army) and had lifted weights recreationally. But life post-injury would mean he couldn’t even swing a softball bat. Powerlifting—which tests the squat, bench press, and deadlift—on the other hand, provides a great physical and mental test that would allow him to compete around his injury.

The moment he got out of the hospital he dedicated himself to powerlifting and retaught himself how to do the big three lifts with his new limitations. The 36-year-old’s best all-time numbers, post-injury, are inconceivable to the average person. Pegg has deadlifted 770 pounds and benched 330. In the squat, where the limited use of his arm is much less of a liability, he has put up a staggering 1,035 pounds. It’s a seriously competitive number, one good enough to get him sponsorship from PowerRackStrength.com.

Pegg is otherwise able to get by just fine. He lives with his girlfriend in Marion, OH, works as a painter for a company that repairs railroad cars, and is able to pick up his three kids.

He laughs a lot and is able to joke about his injuries. He even sent us a picture of the gaping wounds on his arm. You can see that photo HERE but be warned that it is very graphic. The photo is part of a Facebook album of the destroyed Humvee and his injuries which he sarcastically entitled, “What great tourist destinations!” The photo of his arm has a one-word caption, “PWNED”.

The care-free attitude stems at least in part from the fact that Jason knows he got off easy. He also knows that a lot of veterans don’t have the support that he’s been able to find through family and the powerlifting community. Suicide remains a huge problem for returning veterans, with 22 committing suicide every day. Pegg has firsthand knowledge of the epidemic.

“My unit has lost more men to suicide than to combat,” he says.

Social media has allowed him to stay close to the other men in his unit and use humor and comradery to deal with their experiences.

“I want anyone who comes back and has trouble to know they can reach out to their buddies,” he says. “You’re not alone. I know it’s not a conversation you can force on anyone, but we’ve all had similar experiences. There’s no shame in it. There is always someone out there for you to talk to before it gets to the point where you think there’s no way out.”

Follow Jason on Twitter.

You can learn about the Robert Irvine Foundation and it’s support of our military and their families HERE.